4 June 2006

Despite being known in the past as a model of population control, Indonesia is now straining to meet the demands of its booming populace, with unemployment growing and resources being overstretched, writes AMY CHEW

BACK in 1991, Rudy Madanir was a university student assigned to do community service in a village in Central Java as part of his curriculum.

Upon arriving at the village of Pongong, Gunung Kidul, he was greeted by a curious sight: Rows and rows of houses had the words "condom", "pill" and other birth control methods painted on their walls.

"I was taken aback. Every house in the village had painted the contraception used in the household along with the logo of the National Family Planning Agency known as ‘The Blue Circle’," said Rudy.

In East Java, in the regency of Ponorogo, the sound of a wooden gong was struck every evening from 6pm to 7pm to remind women to take their birth control pills in the 1980s.

Such was the efficiency of the National Family Planning Agency (BKKPN), as well as the people’s support for its programmes during former president Suharto’s rule, that the country was held up as a model of population control.

Following Suharto’s ouster in 1998, the Blue Circle faded from view along with the role of the agency to reduce birth rates in the world’s fourth most populous nation with an estimated 215 million people.

From 1971 to 1980, the country recorded a population growth rate of 2.31 per cent. From 1980 to 1990, the birth rate stood at 1.98 per cent. It declined to 1.49 per cent in 1990-2000.

"Population growth rate is still declining but not as fast as before," said Richard Joanes Makalew, national programme officer on population and development strategies for the United Nations Population Fund.

Experts worry that if the trend continues, the country will face a baby boom which will strain its limited public and natural resources.

BKKPN is not operating at optimal level because of a lack of funding and political support.

Following Suharto’s ouster, the country embarked on a devolution of power as part of the reform process. Family planning was decentralised in 2003 which placed funding and implementation of programmes in the hands of local authorities.

Many local governments do not regard family planning as a priority and, therefore, allocate little to it.

Macalew said: "Local governments prioritise physical development, things which are visible to the people, like buildings, to boost their chances of being re-elected."

In the past, the National Family Planning Agency was a department which stood on its own. Now, it has been merged with other local government departments, reflecting the low priority accorded to it.

"In West Kalimantan, I saw the national family planning agency merged with the office of cemetery services to become the Office of Family Planning and Cemetery Services," said Macalew.

"In Puwakarta, West Java, the agency was merged with the civil registration and local elections office," he added.

When Suharto implemented the family planning programme, he succeeded in slowing the country’s high population growth rate because he was committed to its cause and made sure that it received ample funding.

"Pak Harto was committed because he saw population growth as an issue of food security, nutrition and health," said Haryono Suyono, the former head of the agency during Suharto’s time.

Haryono is known as the "father" of the country’s family planning. Contraceptives were given out free to the people during the first 10 years of the programme.

Unlike China, which has a strict one-child policy, the government did not restrict the number of children per family but encouraged each family to have two children.

Haryono said: "With smaller families, the quality of life would improve as people get to have better nutrition and resources."

The government enlisted the help of ulama to implement the programme when it was launched. This proved a crucial factor in its success.

"As Indonesia is a Muslim country, we embraced the country’s ulama and worked with them. The ulama were at the forefront in helping to implement the programme," said Haryono.

But now, family planning is opposed by conservative, religious MPs in parliament.

Macalew said: "Politicians are affected by religious leaders. If the MPs support family planning, it would undermine their political support as it is not popular with religious leaders who view it as going against religion."

Experts expect the effects of the baby boom to be felt in the next 15 to 20 years when they start entering the labour force.

Indonesia is grappling with unemployment which stood at 10.8 million at the end of last year.

The lack of job opportunities will also fuel the exodus of workers to Malaysia and Singapore in search of work.

Every year, 100,000-120,000 Indonesians leave the country for Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong and the Middle East.

Wahyu Susilo of Migrant Care said: "Those figures are for legal migrant workers. We believe the true number of people seeking work in foreign countries is far higher."

According to the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union, there are more than two million illegal workers in Malaysia and 1.2 million who are legal.

Yulienzah, the union’s economic development co-ordinator, said: "The population is growing too fast while the job opportunities here are too few. If you go to the villages, there are many young people who have no work and are seeking to leave the country."

Macalew said there were signs that the country’s infrastructure and natural resources were becoming overstretched.

"Every year, we need more food, more schools, more health services, more housing, more jobs," he said.

"This generation doesn’t have sufficient health and education services.

"The increase in population has also not been matched by the increase in food production; that is why we are importing rice."

By : AMY CHEW

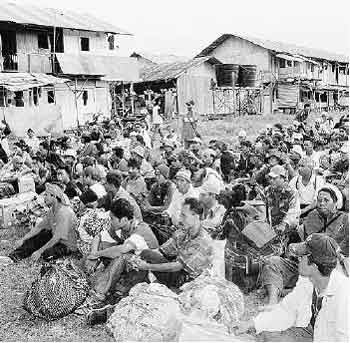

The lack of jobs in Indonesia will fuel the exodus of workers to Malaysia and Singapore in search of work.